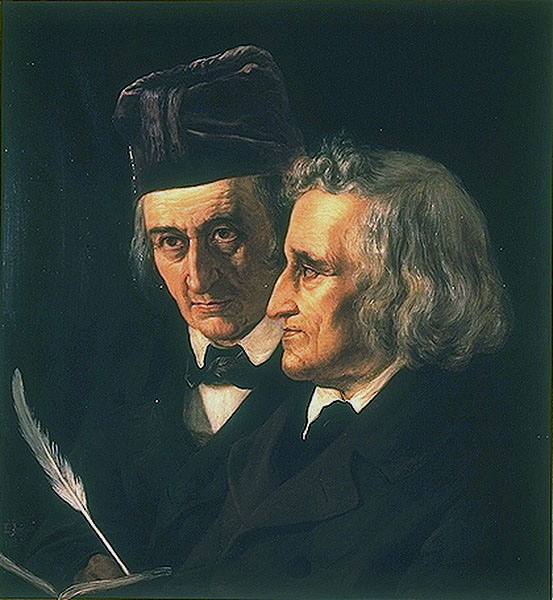

In a previous Letters from Abroad, I wrote about Dr. Seuss and his connection to science fiction. Read it here. I wanted to talk about two other authors that sit at the nexus of children’s books and sff, in this case fantasy. Namely, the Brothers Grimm. The Brothers Grimm are, to make an analogy, something like an early literary species that evolved into both branches of literature, fantasy and children’s books.

And it’s possible they have reached more children even than Dr. Seuss if only because Dr. Seuss, beloved so much by native English speakers, is very hard to translate. While the folktales told by the Brothers Grimm have been translated, I am sure, into almost every language on Earth and read by children (or to children) everywhere. Although whose stories spoke to you more when you were young, that would be a different measure.

“Little Red Riding Hood” (the actual title in German is “Rotkäppchen”, which translates more accurately as “Little Red Cap”), “Rapunzel,” “Snow White,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Hansel and Gretel,” “The Bremen Town Musicians,” and “Cinderella” (called “Aschenputtel” in German, we often forget that the cinder part of Cinderella is meant literally as the cinders in the fireplace which she sleeps besides and which cover her—in German, Aschen for ashes), all are stories written down by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

Of course, the Grimms didn’t invent their stories the way other authors have; they collected them and retold them (although, as I understand it, they nevertheless shaped their versions). Still, Tor.com readers probably know this, but not everyone realizes that there are other versions of their stories, many of them written down earlier, from other countries: Italian versions, French versions, Polish versions, the list goes on and on. (See Charles Perrault and Giambattista Basile, among others. Hi Europeans out there!). In the case of Hansel and Gretel, there is “Nennillo and Nennella” by Giambattista Basile, an Italian version written, I believe, in the 1630s, almost two hundred years earlier than Hansel and Gretel. “Hop O’ My Thumb” (late 1600s from France, I think) also has children abandoned by their parents. In this version it is the father’s idea. (Europeans please feel free to comment below on these versions if you know them and tell us more about them.)

It is interesting to note, by the way, that the Grimms were, at least part of the time, librarians. So, for all you librarians out there, remind people of that every once in a while! Actually, what they did, collecting and organizing stories seems to me like pure library science. (Librarians who know more about library science, feel free to comment).

The versions of the Grimm folktales that children hear today, of course, are sometimes toned down a bit and often rewritten. One fascinating fact for me personally was that the Brothers Grimm actually toned down their own stories. At least, in the original version they wrote of Hansel and Gretel, the children’s parents are their biological parents—their mother, who suggests getting rid of them, is their biological mother, not a stepmother.

Later, the Grimms changed the mother character so that in the final 1857 edition, she is a stepmother. I am still hoping a teacher sometime might read the two versions to a third or fourth grade class and ask them what they think of this change. A kind of literary analysis for elementary school kids! If you do, email me and tell me what happened.

I could talk some about my book here, but there will be time for that later; plus that information is available in other places.

I close with this description of Little Snow White from Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm:

ein Kind so weiß wie Schnee, so rot wie Blut, und so schwarz wie das Holz an dem Rahmen

Which translates as:

a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the [ebony] wood of the [window] frame

We hear at once the folktale quality. I wonder if we will ever return to imagining Snow White in such terms.

I open this up for comments now. Readers out there know a lot about the direct and indirect influence of the Brothers Grimm on fantasy. How does this influence compare to the influence of Beowulf and other stories, much older than those published by the Brothers Grimm? How much of it depends on Tolkien’s own study of these old stories, and his incredible influence? Are the versions of witches, people turned into animals and vice versa, riddling characters, kings, queens, and similar described by the Brothers Grimm the ones that have shaped modern stories, or are Shakespeare’s witches our witches, and are there other seminal historical texts that set up these icons of fantasy literature besides the Brothers Grimm? Finally, how important is it that we hear the Grimm folktales before other fantasy stories—that they are young children’s literature?

Keith McGowan is the debut author of The Witch’s Guide to Cooking with Children, which was named an “inspired recommendation for children” by independent bookstores nationwide. He is published by Christy Ottaviano Books, Henry Holt & Company.

I don’t know that I would really characterize the Grimms as librarians. It’s true that Jacob worked as a librarian over the years, and Wilhelm may have, but they were primarily and most importantly philologists and lexicographers. Indeed, had they never collected a single tale, they would still be famous for Grimm’s Law and the first German dictionary.

The Grimms are certainly an influence on Angela Carter, who I would count as a great fantasy writer (I tend to consider magical realism as how critics describe good fantasy). Much of Neil Gaiman’s work shows an influence from folktales in general – and the works of Grimm and Perrault in particular.

I think the grotesque end of fantasy owes a debt – whether conscious or not – to fairy stories.

The UK paper The Guardian’s been running a series on fairy tales over the past week. In addition to re-printing a number of excellent translations by Phil Pullman, Alison Lurie and others, they’ve also printed an excellent series of commentaries by the above authors and Adam Phillips, AS Byatt and Hilary Mantel.

The stories and commentaries are linked from here:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/oct/14/fairytales-wisdom-folly

Incidentally, one of the most chilling and (to my mind) strange Grimm’s stories is one of their lesser known ones – The Almond Tree

http://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/the_almond_tree

Well worth a look if you haven’t read it.

I have found that the best site on the web for information about fairy tales (Grimms Brothers and others) http://www.surlalunefairytales.com. There are annotated tales, famous illustrations, different versions of the tales, and a lot of other stuff.

My Mother has been writing Hard SF novel set on a Planet of German extraction and the Grimm’s fairytales are all over the place both as set dressing and comentary. Hansel and Grettel was used in the movie “I, Robot”. I’ve seen a delightful take on Cinderella as a chapter in the Japannes light novel series “Full Metal Panic!.” These stories are some of the basics of literiture all over the world.

I think it is importent to recognize that the original stories the collected were…umm pretty grim, even after they toned them down. I think the 2005 movie “The Bothers Grimm” (One of Heath Ledgers and Matt Damon’s finast performances) gets the mood very right. As does the “Fables” comic series, and “Jim Henson’s Storyteller” series.

wow, jim henson’s storyteller.

that was an awesome show!